Mathematics is a subject that tends to frustrate students till no end. Even as a student that is interested in majoring in mathematics, I will say it irritates me at times as well. However, I want to delineate a problem that made me fall for the discipline, with the aim that you will as well, or rather at least become more intrigued in learning about the field.

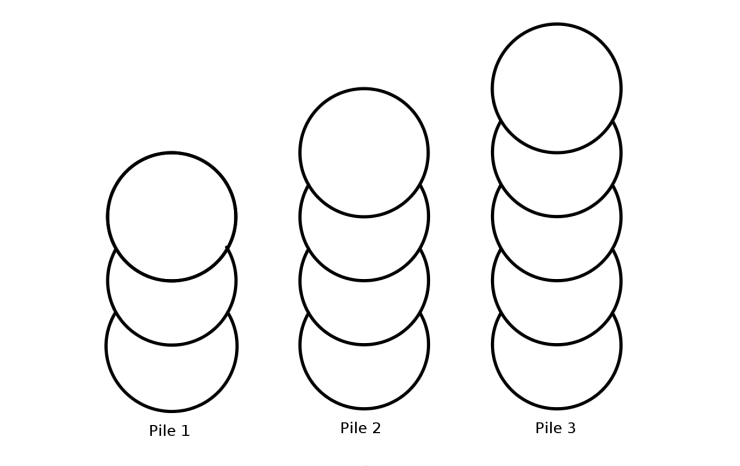

What is that problem you ask? It is combinatorial idea of Nim. Within this concept, two players alternatively take turns in removing, or rather “nimming” tokens from a set of piles. To understand Nim, an illustration of this problem would be rather appropriate.

Setting It Up

Take some coins for instance, and place twelve of them them in a row, one next to the other. Now, in Nim, the rules and layout are up to the player’s digression, though in this instance, courtesy of Matt Parker from Stand-up Maths, let us say the players can remove one, two, or three coins per turn. The player that takes the last coin wins.

Seems simple enough… till it isn’t. It would be ideal to see an example on why.

Twelve coins are set in a row, and two players, Oliver and Alice are ready. Now remember, the aim is to take the last coin. Oliver decides to start, and takes two coins. Now, ten coins remain. Alice decides to take two as well, leaving eight coins left. Oliver takes three coins, leaving five. Alice thinks for a moment, and takes one coin. Four coins now. Oliver stares at the coins, and realizes that he is lost. If he takes one coin, Alice takes three. Two coins, and Alice takes two, and if three coins, Alice takes the last one.

So, what’s the strategy, if any at all? Do the players take coins at random and see what works? Not completely. Take another look the example I wrote out. We noticed that Oliver lost once there were four coins left, as regardless of if he took one, two, or three coins, Alice would always be able to take the last coin, which wins. This is where the strategy comes in. In order to be in the position to take the last coin, we need to set up the endgame where four coins remain, and that it is the opponent’s turn when that situation occurs. In order to set this endgame, we need to the coins to be taken in multiples of four. Though, there is another issue. If Oliver starts, then Alice can take in a way that does not lead to a multiple of four. For instance, if Oliver starts with taking one coin, Alice can also decide to take one coin, and ten coins remain, which is not a multiple of four. The strategy seems to not be foolproof…

However, we can offer Alice to start. As we all know, ladies first. With this, depending on the number of coins Alice decides to take, we can take the set amount of coins in order to set a multiple of four with the amount of coins that remain. If she takes one, we take three. Two, and we take two. Three, and we take one, all situations leaving eight coins left, a multiple of four. Do you notice the pattern? Now, if Alice insists that you start, you can add another coin to the set, (without her noticing) now thirteen, and then take that same coin out, leading to the ideal scenario, where there are twelve coins, and it is Alice’s turn.

Different Shapes and Sizes

Now, this is not the only instance of Nim. There are numerous interpretations of it, from Grundy’s game to Bounded Nim, as well as varying layouts of Nim, such as sets of piles with differing amounts of tokens. These interpretations are stated in-depth, courtesy of Ryan Julian from The Madison Math Circle.

In particular, I fancy the variation of Nim named Mis´ere Nim, which is almost identical to the original idea, but the player who takes the last token loses. Though, instead of describing another iteration of Nim with twelve tokens, let us instead run a program that switches the number of tokens per trial.

import random

def pick_for_computer(stones):

# returns the computer's choice of stones

if stones == 2 or stones == 5:

return 1

elif stones == 3 or stones == 6:

return 2

return random.randint(1, 2)

def pick_for_human():

# returns the human's choice of stones

removed = 0

while removed != 1 and removed != 2:

removed = int(input("Enter the number of stones to remove (1-2): "))

return removed

def show(num_stones):

# displays the current number of stones

picture = "O " * num_stones

label = f"({num_stones} stones left)"

return picture + label

def initialize():

# returns the starting size of the stone pile

return random.randint(10, 16)Above is code for a program, courtesy of Khan Academy, that contains the logic of the computer’s and human’s choice of tokens, or in this instance, stones to take. If you notice, the computer has a defined specification to decide the amount of stones to take depending on the pile of stones at hand. Although, this code does not initialize a pile of a random amount of stones per trial ran. Let us add that in.

import stones

print("Remove 1 or 2 stones from the pile. The player who picks the last stone loses.")

pile = stones.initialize()

is_user_turn = True

while pile > 0:

print(stones.show(pile))

if is_user_turn:

removed = stones.pick_for_human()

else:

removed = stones.pick_for_computer(stones)

print(f"Computer removes {removed} stones.")

pile -= removed

is_user_turn = not is_user_turn

if is_user_turn:

print("The computer picked the last stone.")

else:

print("You picked the last stone.") There! With this code provided, I prod you to run it your own, and experiment with all the variations that arise, and the strategies that unfold as a result. It is quite captivating I will say!

Well, seems that mathematics is not so bad after all right? Throughout all the ups and downs I faced in this subject, I still recall when I was introduced to Nim, and the rabbit hole that I went through to understand all of its nuances. Albeit I was not a a mathematics person at the time, learning about this concept did trigger my curiosity, and if all went well in this post, I am optimistic yours did too!